Cleveland Orchestra, we finally talked about my subscription on Saturday, and I told you the news: I am not renewing this year, but we needed to talk.

It’s not me, it’s you.

The concerts are great. I’ve loved the concerts. I’ve been attending subscription concerts since 2000, with a long break in there when I lived out of town, but for many years I couldn’t imagine living in Cleveland without being a subscriber. In fact, attending your concerts has spoiled me for any other orchestra, I daresay. My wife and I once subscribed to the nearest symphony orchestra to where we were living–a 120-mile round trip–and I was glad to go, but there were two concerts that were just bad now that I’ve heard you (and Chicago, and the London Symphony Orchestra, and Cincinnati, and Columbus, and Nashville… there are other fish in the sea, even if they aren’t you). I wish I could afford better seats, but at Severance, all the seats are good enough to give a fantastic musical experience, even if you have to climb a small mountain to get to them.

I’ve heard and seen some amazing things the last few years: Abrahamsen’s Let Me Tell You, Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, symphonies by Mahler (although not as many as I paid for), Shostakovich, and Sibelius, and Respighi, and Richard Strauss’ Alpensinfonie. Even when I’m a little bit disappointed, like with your Rite of Spring last year (so polite!), it isn’t because your standards aren’t high, it’s because I live in a different world where orchestra music has scrapes and scratches and I forgive them because I make music with people who can’t devote all their time to it, even though they wish they could, and work as hard at it as they can.

The problem isn’t the performance, though. I want you to know that.

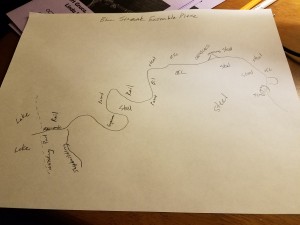

Last year, I built my own season. There wasn’t a package that wouldn’t have had me trading in everything. You know there are things I like, and things I avoid. Give me new, give me big, give me challenging. I have a list of pieces I want to hear you play, and I’ve been checking them off. Since I’ve been 40, I think of it as my bucket list. I can’t afford all of the concerts, or even half of them. Four concerts is what it comes down to, and last year, you threw me a ticket to the gala, which was, of course, well-performed, but not really music I was excited about. It was an orchestra seat, and I never sit on the first floor, but the gala convinced me that maybe I should once in a while. I digress. I come alone, which isn’t ideal sometimes, but we have two small kids who can’t come, and my wife just isn’t interested enough to justify the extra expense. I consider it to be professional development, not entertainment, and I write off all the expenses of going (study scores, recordings, mileage, parking, tickets) on our income taxes. It’s a big deal for me to go, and I look forward to it, and it, frankly, disrupts things at our house by putting more work on my wife as she picks up the slack. But it’s worth it, to me. So worth it. I even leave early and come to the talk. These are not the things that are making me not renew, but rather the circumstances of my attendance, and I have long been willing to deal with them, and since I moved back to Northeast Ohio, I have gone to subscription concerts every year, and subscribed for the last five years. Last year, I even used one of my precious slots to come hear Mitsuko Uchida play my favorite Mozart concerto (No. 20), something I have eschewed before because of my personal tastes, but felt like I needed to try as a professional–experience part of a collaboration that will be legendary. (It was good. It was so good. But not for me.)

So here are my problems:

In January of this year, I had a ticket to see Mahler’s Ninth Symphony on a Friday night. For once, a friend and I had made plans to go together. My friend bought a single ticket. Then the weather turned, as is wont to happen. We consulted, and decided to stay home and live to see more Cleveland Orchestra concerts rather than risk the roads. It’s after 5pm by this point. Guys, you let my friend change to Saturday night, but told me, a long-time subscriber, that I would have to eat the ticket that I had paid for back in August. Mahler’s Ninth is on my bucket list, and now it will have to wait. It would have been great–I know it was, because my friend told me how great it turned out to be on Saturday. Seriously?

Now that seems a little bit petty, so let’s talk about programming choices. Let’s talk about last season, the Centennial season. Sometimes, I feel like you go into “dog and pony” mode. All of Respighi’s Roman tryptych on one concert, for example (brilliantly played, of course). The last couple of weeks of this season–your big centennial moment–had Tristan and Turangalila and a week of all nine Beethoven symphonies. Don’t get me wrong: I love Beethoven. I get that Beethoven is the reason that any orchestra exists in its present form, and that any orchestra needs to play a lot of Beethoven. But as your 100th birthday present to the world? As a way to mark what you have accomplished and look to the future? If I want to hear all nine Beethoven symphonies, I can do that in so many ways, from streaming, to popping in the complete set by Toscanini I bought years ago (or picking up the versions you recorded with Szell), or, honestly, by attending concerts at Severance and Blossom. How many of those were you going to play anyway? Three, four, five? Seems likely. I’ve heard your Beethoven, and it was transcendant (the Ninth at Blossom a few years ago). I actually went to a Beethoven Ninth last year because a friend of mine was singing with the Cleveland Philharmonic, and as a conductor of a community orchestra, I just wanted to see what would happen. Yes, I schlepped all the way to Westlake to hear a pretty darn good rendition in a decent space, and I took my parents, and we didn’t have to pay to park, and my chair was more comfortable. I mean, it still wasn’t you, but it wasn’t a terrible experience at all.

My point is, you shot your centennial wad on celebrating the past, playing music that every community orchestra in the country goes after, that, let’s face it, your musicians have memorized at this point. This is the 1992 US Men’s Olympic Basketball team or the 1927 Yankees playing high school ball. This is Bobby Fischer playing chess on his smartphone. Yes, program Beethoven. But as your big thing? As your notch in the rock? Seriously? If nothing else, the disappointment when I opened up that brochure a year ago was almost enough, but there were some bucket list things in there, too for me: Messiaen, the Mahler (see above), Rite of Spring (see above), Jonathan Biss playing Sciarino (with Bruckner), and some I couldn’t go to because there wasn’t time or money. So I bought the tickets.

But do you know? I was a college freshman in 1994 when the Cincinnati Symphony turned 100. Do you know what they did? The commissioned a new piece for every subscription weekend. 25 or 30 pieces by living American composers. (They called them fanfares, in homage to the group of commissions they made 50 years earlier during the Second World War. One of those pieces? You might have heard of it: Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man.) So anyway, as a freshman with a card that got me $7 tickets (seven dollars!!!–the sticker shock when I found out what full price at the symphony meant!) and a bunch of fellow music majors to split cabs with, I got an education on the state of composition in the US. Local composers. National composers. Even one who had been commissioned 50 years earlier! (Short on women and people of color, but more on that later). Cincinnati acknowledged their past in some big ways, but they also pointed toward the future, in essence telling us that they would be around for another century. The audience in Cincinnati was much more conservative and much more blue-haired than the audience at Severance. Music Hall was not nearly the venue that Severance is (although I haven’t been back since the renovation was done). Did you really let Porkopolis outdo you on this?

The Los Angeles Philharmonic turns 100 this year. And they have commissioned fifty new pieces, with an appropriate range of composers in terms of both style and background. I couldn’t believe the list–I felt like I was the only composer who didn’t get a commission on this project. Old, young, white, not-white, male, female. Every audience member and every potential audience member can connect with one of these people. I mean, if LA can pull this off in a town with a reputation for chintz and superficiality, surely Cleveland could have done such a thing, and with more grace and good-old Midwestern-meets-Mitteleuropan rigor, right?

And then this year. Where are the local composers? Where are the composers of color? Where are the composers who aren’t dead white men? I haven’t made a big deal out of it, but the orchestra I conduct, which puts on three concerts a year, has a piece by a female composer on every concert this year. That means we are programming 300% as much music by women as you have on your Severance series. A community orchestra. And honestly, not the best one around, and certainly not the one led by the best conductor around. But you know what, I just did it. I don’t have to explain why we’re doing it (or at least I shouldn’t, but here goes: lots of good music out there by women that we haven’t played yet; half our audience is female; more than half our orchestra is female; there are things a female artist has to say that need to be said; they are just good pieces; there are centuries of oppression and suppression to make up for… need I go on?). I’m still working on more music by people who aren’t white–I’m hoping to secure funding to be able to afford William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony this year. When are you doing Black composers other than on Martin Luther King Day? Your centennial season was also the 50th anniversary of the Hough Rebellion–your next door neighbors. Couldn’t you even acknowledge that with one piece on one subscription concert? It actually would have fit in well with your Prometheus theme and Beethoven the revolutionary! And there are great composers who have and do call Northeast Ohio their home. Don’t you think that the audience would connect with their work? Ernst Bloch ran the Cleveland Institute of Music. William Grant Still attended Oberlin. Donald Erb. Keith Fitch. Jeffrey Mumford. Margaret Brouwer (we played her last spring, and then she sent the parts we used to the Columbus Symphony, who apparently do know how to look around themselves for inspiration). James Wilding. Clint Needham (Albany and Akron know how awesome he is). Larry Baker. Nick Underhill. Frank Wiley. And none of these people are just wannabes like myself, and they all ache to have their music performed locally. They have awards and major performances and have been recognized. They are the kind of composers who appear on Cleveland Orchestra programs but don’t register outside the region, and you can change that by championing them. The Cleveland Orchestra does not have to be an island of Europe in the middle of America.

I’ve also spent this year following the unfolding scandals throughout the classical music world as part of the #MeToo movement. As it happens, I also took the time to read The Cleveland Orchestra Story by Donald Rosenberg. I’ve been around the music world long enough to know about the open secrets–my alma mater in Cincinnati finally dealt with one of those this year, and let me tell you that as an undergrad trombone major, I had heard the rumors about that particular predator and his students. So Levine, yes. That was a long time ago, but talking to people who were around then, it was pretty clear what he was up to, and you all enabled it. You all gave him his start and let down generations of young musicians–again, the future of our art form. It could have been nipped in the bud, but in the name of art and I-don’t-know-what-else, you let it go. It was before my time, though, so I can’t really understand the decisions, and most of the people who let it go on are long gone. But Preucil. A great player, and a great caretaker of the string section, of course, but you’ve been paying him nearly a million dollars a year to abuse his position and the power it gives him over young musicians. And it’s been more than a month now, and you’ve still only suspended him with pay. I know there’s a union agreement, and I know there’s due process, but come on. Have you seen the Google search results for “Cleveland Orchestra concertmaster?” This doesn’t look good, and people have certainly been fired for less, and you know what? He will be fine, because you have been paying him nearly a million dollars a year.

So, I’m not subscribing. That’s why.

I might come to a concert or two (John Adams and Jennifer Higdon are both high on my list; I actually wish I would have gone to Tristan last year, because how many opportunities do you get, honestly, but it wasn’t a convenient week for me). I will definitely check out some of the other great classical music going on in Cleveland that I have been missing because I’ve prioritized your concerts: Apollo’s Fire, No Exit, Quire Cleveland, Akron Symphony, Cleveland Chamber Symphony. Maybe I’ll take a trip to Pittsburgh and see what I’ve heard on the radio for many years with the Pittsburgh Symphony. Possibly some things at CIM, where the orchestra did a by-no-means-flawless, but exciting Ring without words last spring under Brett Mitchell, a Cleveland Orchestra alum who I really admire.

There are, of course, other fish in the sea.

I’ll be back. I can’t stay away, because when you have one of the world’s great orchestras playing 20 minutes from your house, what else can you do? (I was stupid and never went to a Cavs game while LeBron was here, but basketball isn’t my career.) So keep sending the brochures and flyers, and I’ll keep telling my students to head on down (but I’ll tell them why I’m not), and we’ll see each other when we see each other. But just know–it’s not me, it’s you.