An excerpt from Chapter 5 of my book Music: Notation and Practice in Past and Present, currently in press.

The conception of the staff as a form of the xy-coordinate plane is adequate for an understanding of the notation of pitch events and their temporal relationships. However, music is far more subtle than the four elements of melody, harmony, tempo and rhythm that can be described in this way. In fact, staff notation as we have studied it ignores the musical element that frequently gives the first and most basic aural cues to listeners: timbre. Many listeners who fail to be excited by the use of unique scales, obscure keys, unorthodox meters or complex chords are instantly enthralled by the sound of familiar or favorite instruments or the specific timbral qualities of the voice of a beloved singer. The system of musical notation simply cannot be considered complete without a means for indicating timbre.

For centuries, though, there were no such indications in Western musical notation. While the earliest forms of what would become modern notation date back to the 10th century A.D., no composer indicated what instruments were to play the specific parts in a score until Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554/1557-1612) published his Symphoniae Sacrae (1597, 1601), which indicated timbre by naming the desired instrument to the left of each staff in a system, or group of staves. For music prior to that time, performers and musicologists must often rely on other clues left by the compositional process. The inclusion of poetic text, for example, indicates that a composition was likely for voices, although it is always possible that instrumentalists would double the vocal parts, as continues to be the case in much music written to this day. This practice is prevalent in Protestant hymnody, where it was traditional for the music to be written in four vocal parts (soprano, alto, tenor and bass), but doubled on a keyboard instrument such as piano or organ. Specific melodic or harmonic figurations may indicate that a composition was intended for a specific instrument, such as a keyboard instrument or a fretted string instrument. In general, however, during much of the history of music, music, whether notated or not was performed by the available forces at any given moment. It is remarkable that the first composer to call for specific instrument worked in Venice, one of the most prosperous cities at the time, where he supervised the music for St. Mark’s Cathedral, the central church of the city. The musical forces available to Gabrielli were likely some of the most reliable, professional and well-paid in Europe, and it has typically been in environments such as this that musical experimentation thrives and new standards are set that eventually become adopted throughout a culture.

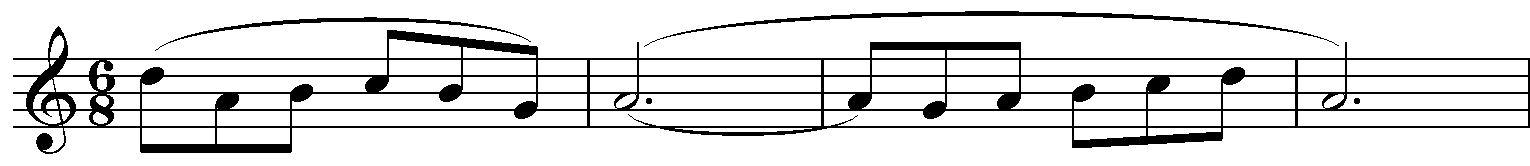

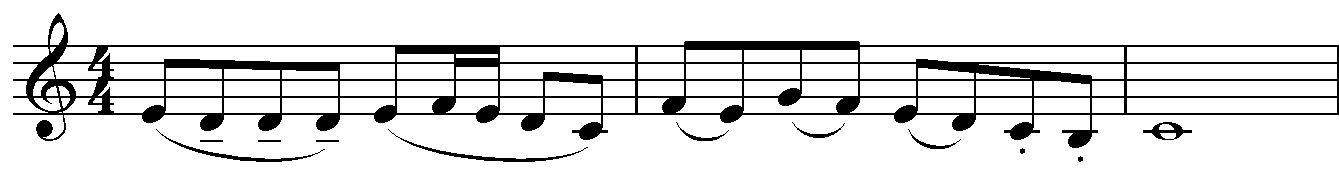

It is likely that an experienced musician, presented with an unlabelled instrumental part for a standard instrument, could identify the instrument being called for by investigating certain factors. Instrumental range is a possible clue, as all instruments have at least an absolute lowest pitch, and while their range may theoretically extend upward to infinity, there is usually a generally-accepted upper limit to the pitches that a standard instrument can play. For example, the modern flute can play no lower than B3, and only to C4 on some student models[1]. Its upper range extends to approximately C7 for professional players. In addition, as with all woodwind instruments, it is common to write trills, in which a player rapidly alternates between two notes a step apart, for flute. However, some notes are more easily trilled than others, and an astute composer will avoid the difficult trills while utilizing the more convenient ones. If the hypothetical mystery part, then, had no notes below C4, but a range extending up to B$6, all the while treading delicately around the more tricky trills (such as that between C4 and D$4), it would be reasonable to conclude that it was music for the flute. This music would be said to be written idiomatically for the flute.

Idiomatic writing for an instrument or voice is crucial to successful composing and arranging. While more basic music is generally playable on any instrument if transposed into the correct range, more complex and difficult music can quickly overwhelm the abilities of even a professional performer if utmost consideration is not given to the unique properties of an instrument or voice. For vocal music, it is even reasonable to compose with a specific performer in mind, as human voices are as wondrously varied as human faces. For example, British composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) had a life-long collaboration—both personally and professionally—with tenor Peter Pears (1910-1986), resulting in several sets of songs, operatic roles and the incomparable Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (1943) being composed with Pears’ somewhat unremarkable voice in mind. These works reflect the limitations and advantages of Pears’ instrument and, like others composed for specific performers, they must be approached with this in mind. The Britten-Pears collaboration has been the subject of much musicological study, and is a prime example of the ways in which a composer’s life can impact his work and vice versa.

Composers also write for specific instrumentalists. For example, Aaron Copland (1900-1990) composed his Clarinet Concerto (1947-9) on a commission from clarinetist Benny Goodman (1909-1986). Goodman, better known for his jazz improvisations than his classical performances, felt a responsibility to add to the repertoire for his instrument, despite his own feelings of inadequacy about his ability as a classical performer and admitted discomfort with notated music. Copland’s concerto, then, is scrupulously notated and, while not in a jazz idiom, works very closely with what is natural to the clarinet while at the same time providing a piece worthy of Goodman’s substantial technical prowess. Goodman has not been the only performer to feel compelled to contribute to the repertoire for his instrument. In the 19th century, virtuoso violinist Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840) not only composed music for himself but commissioned others, with the result that Paganini’s revolutionary technical skills, many of which were innovative developments for the instrument, became standard violin technique within a few generations. In the late-20th and early-21st century, a generation of gifted trombone players, such as Swedish virtuoso Christian Lindberg (b. 1958) and the American Joseph Alessi (b. 1959), has been creating a repertoire for their instrument by commissioning and performing new music. These new pieces will impact the study of the trombone for generations to come as students begin to view these new works as the standard aims of serious study on the instrument.

Similarly, a performer may possess unique or innovative abilities that a composer wishes to exploit in a musical composition, or that a performer may employ in his own music. Vocalist Bobby McFerrin (b. 1950) possesses a miraculous instrument capable of an enormous variety of vocalizations that he has employed in jazz, popular and classical-style compositions. Similarly, soprano and composer Cathy Berberian (1925-1983) possessed a vocal instrument whose range, expressiveness and accuracy inspired not only her own compositions, but also those of her husband Lucciano Berio (1925-2003) and many other composers. The ongoing collaboration between composer and performer can be as vital and important as that between two actors or an actor and a director with onscreen chemistry (Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan, for example, or Jack Lemmon and Walter Mathau, or Jimmy Stewart and Alfred Hitchcock), and it can define careers and musical legacy, as is currently being seen in the collaborations of composer Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960) and soprano Dawn Upshaw (b. 1960), or composer Magnus Lindberg’s (b. 1958) on-going work as Composer-in-Residence with the New York Philharmonic. For this author, who is trained as a composer, collaboration with a performer who gives significant practice time to a new piece is a joy. When a performer becomes as emotionally involved as the composer with the new piece, however, the experience is as thrilling—and absorbing—as a new love affair.[2]

It is likely that most composers in the era before 1600 simply knew their performers personally, never intended to distribute their music widely and wrote for the individual at hand. In our technological, text-saturated world, duplication of the written word (or composed note) is cheap and easy. A composer can write a piece today that will be played, sung or heard by thousands tomorrow, making it impossible for the composer to know every performer—or potential performer—personally. Every musician’s abilities are different, and every musician’s musical language is slightly different. This is the challenge that the composer of music for a specific timbre faces, then, and the answers to this challenge are highly varied, and often quite subtle.

[1] The flute of Mozart’s day had a lowest note of D4. The additional notes are operated by keys in what is known as the foot joint of the flute, an extension of the main body of the instrument. Student-model flutes typically only have two keys in the foot, allowing C#4 and C4, while professional-model instruments add a third key to bring B3 into action. A few flutes have a fourth key to allow the performer to play B$3.

[2] In an interesting case of emotional transference, German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883), who enjoyed a coterie of musicians who were passionately devoted to his controversial operas, had a tendency to seduce the wives and daughters of the men who conducted his music. Such was Wagner’s spell that at least some of these men continued to support Wagner’s musical efforts after being cuckolded.