I’m amazed that it’s October already.

I was feeling very behind on some things for work and school, and my wife, Becky, got tired of my grumpiness about it and gave me the incredible gift of time last week: she took time off from her job so that she could be around and give me some relief from some parenting duties. I took advantage of that time to get back into my morning composing routine: waking up an hour ahead of everyone else to work. It feels good to be back on it. Plus, I was able to work ahead on some of the things I normally do on Fridays and clear the decks for most of a full day of composing this week. It felt good: too good… because it had me thinking about how it might work if I did that every week, and spent that day just building my composition business. It seems possible, but risky, but possibly very rewarding.

I suddenly find myself with multiple projects. Last month, Ted Williams of Choral Spectrum contacted me asking for Christmas music. There is a history there: eighteen years ago when I was living on the West Side of Cleveland, I joined that ensemble, starting the same concert cycle that Ted did. They performed one of the pieces that I submitted as part of my grad school applications, and I haven’t done a great job keeping in touch, but I’ve been in contact with Ted now and then. I found a nice, short poem by Ella Higginson called “Christmas Eve,” and suggested it as an original piece. I finished it this week, after creating a draft in my parents’ dining room in September, and rehearsals will start on Monday, for premiere performances in December.

Next, I’m returning to the first piece I wrote after graduate school, the fourth in my series of sonatinas for woodwind instrument and piano, in this case, oboe. There is a connection to that same time with Choral Spectrum, because I used the bassoon piece, the first in the series, as a part of grad school applications as well, including a recording with fellow Spectrum member Andrew Bertoni on the piano part. I’m now reworking the oboe piece, which has never been performed, for Justine Myers, and we are hoping for a performance on a Cleveland Composers Guild concert this spring. As I was working on both these pieces, I had advice from Donald Harris in my mind: “let the music breathe.”

Then, to the carillon project, I suppose. Last summer, Guild members had a tour of the McGaffin Carillon with George Leggiero for a collaboration that will feature our compositions for the instrument this fall. Fall is here, so I need to get started on mine.

After that, it will be the band piece I’m writing in memory of Chuck Frank for the Lakeland Civic Band . I have an idea for a wordless vocal soloist and Heidi Skok is on board, so while that part will be cued in the instrumental parts, it will be a great way to feature one of our great local musicians.

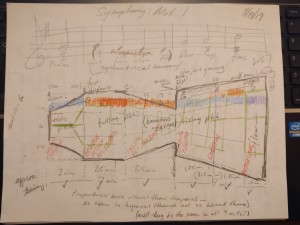

And then… I want to return to the symphony. Delayed first by COVID, now just by my procrastination.

The amazing thing is that these projects represent the fruits of a decade or more of collaboration, networking, and community-building. My goal since returning to Ohio has been to become a Cleveland composer, and I feel like I have achieved that, at least at the moment.

Now to the title of this post:

Two ideas for analytical or compositional tools came over my transom this week.

The first was when I went to observe Scott Posey’s Acting I class as part of my duties as a College Credit Plus faculty liaison. I had watched him work with his students at Lake Catholic before, but he started his class with a warm-up and review of something called “effort-shapes,” coming from Laban movement theory. This was immediately highly suggestive to me as a way to think about the physical expression suggested by a passage or piece of music. I also wonder if there is any similarity or connection to Dalcroze eurhythmics, which I have never had the chance to study.

The second is from a YouTube video. I’ve been watching architecture videos by Stewart Hicks lately, and his video on Francis Cheng’s Form, Space, and Order really struck me. Where Laban seems to suggest itself as a tool for medium-scale analysis, Cheng’s five basic building plans (centralized, linear, radial, clustered, and grid) are highly suggestive of ways to understand the overall structure of a larger piece. Of the standard forms, fugue would be centralized; sonata would be regular; rondo would be radial; variations would be radial or clustered?; and something with a repeated bass or harmonic progression would be grid. Perhaps? Something to consider… Orchestrating or arranging for large ensemble often feels like working with a grid as well. Penderecki’s Threnody suggests a clustered approach; while Lutoslawski’s Fourth Symphony is more radial. Intriguing set of possibilities.

Then, yesterday, we went to Cedar Point. My approach to fun at theme parks is a little different than most people’s, I suppose, but I enjoy looking at how the place works, and at how people interact there and flow throw the space. I find that standing in line for rides gives plenty of time to watch how those rides work, and how people interface with them, and to think about what I’m seeing. Recently, one of my contacts on Twitter posted Baudrillard’s thoughts on Disneyland, and that was running through my head. While Cedar Point is in many ways a theme park in search of a theme (beyond, as Noah and I discovered, “Eat. Ride. Repeat”), it functions in much the same way Disneyland does on a technical level. This may not be true from a cultural standpoint, though. Disneyland also does not have nearly the history and layers that Cedar Point does, where there is an 80-year head start and any number of callbacks (such as the Blue Streak roller coaster) to earlier eras of American pleasure-seeking. I’ve decided that I’m going to have to read Simulacra and Simulation.