An excerpt from Chapter 4 of my forthcoming book, Music: Notation and Practice in Past and Present:

There is an unfortunate tendency among music readers to view rhythmic notation as defining points of sound that occur at discrete moments. On certain instruments, this is effectively true. For example, once some percussion instruments are struck, there is very little the performer can do to alter the resulting sound, which at any rate, has a relatively short duration. This is certainly the case for some drums, such as the snare drum, and for some of the idiophones such as the claves, woodblock or anvil. For nearly every other instrument, though, including the piano, guitar and the human voice, a note indicates not only an attack, or the start of the sound, but also a release, or an endpoint. In addition, performers may have some control over a sustaining, or continuous middle portion, of a tone, or the decay of a sound, the resonance that continues after a release point. While some aspects of these envelopes are inherent in the timbre of an instrument, others can be effected through developed instrumental or vocal technique. For example, the timbre of the piano has very little sustaining quality—as soon as a note is struck, the sound begins to decay. But through the use of the damper pedal (found on the right on modern pianos), the decay can be allowed to persist instead of being cut off when the key is allowed to return to its original position. This ability has largely defined the sound of piano music for the last two centuries, and a piano without a functioning damper pedal is not a functioning instrument any more than a car without brakes is a functioning vehicle.

The act of shaping the attack, sustain, decay and release of notes is known as articulation, and the art of articulation varies to a greater or lesser degree on every instrument. It is crucial for an aspiring musician to study and understand the technique of articulation on her chosen instrument, and within various styles. Much of what constitutes a style is often a tacit agreement on how to apply articulations to written or improvised music.

Despite the differences in articulation technique between instruments, a reasonably standard set of symbols has developed in written music to allow the composer some control over certain aspects of the shape of notes. These symbols really alter any of several different musical elements—most often rhythm or dynamics, other times melody, and occasionally timbre. Their meanings vary slightly between instruments and styles, but some generalizations about each symbol can be made.

The slur is a symbol with several different meanings, depending on the instrument or voice for which music is written. Its first use was with notes in vocal music that employed melisma, the technique in which a single syllable is sung over two or more notes. In this case, as in Figure 29, the slur indicates exactly which notes are involved in the melisma, and does so more precisely than the lyrics below the notes can do.

Figure 29: Indication of melisma in a vocal part using a slur. The notes will be sung with the words “A melisma,” with the melisma occuring on the syllable mel.

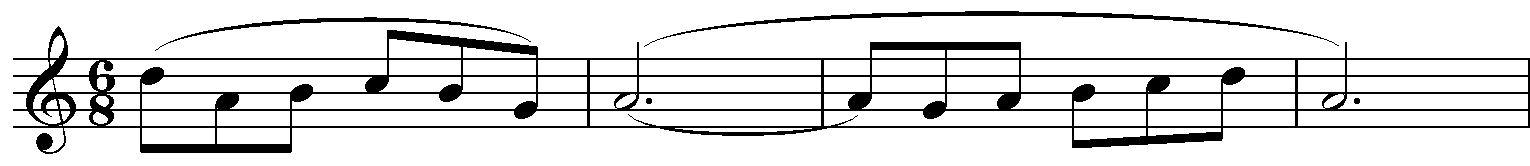

Woodwind and brass players, whose approach to phrasing and articulation is similar to singing in many respects, also use slurs to group notes into unbroken (or slightly-broken) streams of sound. In Figure 30, a passage for clarinet, the first note under each slur is given a relatively pointed attack with the tongue. For the subsequent notes, the air continues to move through the instrument without interference, while the fingers work keys and cover or uncover holes to change the pitch. At the end of the last note, either the tongue or the breathing apparatus may be used to stop the air.

Figure 30: A passage for a wind instrument employing slurs. Only the first and seventh notes would have tongued attacks.

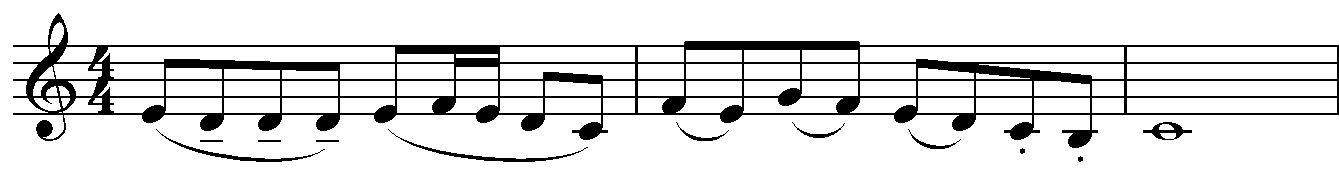

For bowed stringed instruments, slurs indicate the use of the bow rather than the tongue or airstream. All notes under a slur will be played without changing bow direction. In Figure 31, for violin, the player would play the first four notes without changing direction, then reverse course for the next five notes. String players often use the Π and V symbols for downbow and upbow, respectively, in which the right (bow) hand moves in the stated direction, adding further control over attack and sustain envelopes. In addition, other articulation symbols may be used in combination with the slur in writing for strings, often indicating the degree to which the bow should stay on or bounce off of the string at the end of each note.[1]

Figure 31: A slurred passage for a bowed string instrument. The bow would change direction on the first, fifth, tenth, twelfth, 14th, 16th, 17th and 18th notes.

Some instruments, such as piano, guitar and many percussion instruments, have little control over the sustaining power of their notes. The result is that slurs for these instruments are most removed (although not completely separate) from their meaning for the voice. For guitar, a slur indicates that the performer is to pluck the string for the first note with the right hand, and then either “hammer on” (articulate the second note by pressing a higher left-hand finger onto the same string), or “pull off” (change to the second note by lifting up a finger to lengthen the string). The ability to slur on guitar, then, is much more limited than on most instruments.

In music for the piano, which also has limited sustaining power, a slur generally indicates a legato approach to the notes under the slur, meaning that the release of a note is delayed until the finger playing the next note can be put down, usually with a sense of heaviness in the wrist that allows one note to effectively blend into the next.

Slurs for most percussion instruments have only the most basic meaning, but one that is really at the core of the idea of the slur. In its most basic form, a slur indicates musical phrasing, that is, it shows a player that a group of notes is meant to be a single musical idea. This type of slur is frequently combined with the other types for all instruments, and it is typical of many styles to modify the tempo at the beginnings and ends of slurs to allow performers to breathe.[2]

Figure 32 shows the notational difference between the slur and the tie. Several visual cues can be used identify which symbol is being used, notably that the tie always connects two adjacent notes that are on the same line or space on the staff, while the slur may connect any number of notes. There are also slight engraving differences, namely that the ends of a tie are closer to the heads of the affected notes, and the overall depth of the curve is shallower. Slurs generally point to the heads of the first and last notes, and are found on opposite sides of the note from the stem. Two important exceptions, however, should be noted: When a slurred passage begins with a stem-up note and ends with a stem-down note (or vice-versa), the slur is drawn above the notes. And when two voices appear on a single staff, any slurs will connect stems instead of noteheads.

Figure 32: Slurs vs. ties. In each measure, the first two notes are slurred while the second two notes are tied.

Several other standard articulation symbols appear in contemporary notation, each with a slightly different meaning on every instrument. A good instrumental teacher will be able to couch their meaning in terms of instrumental technique rather than precise rhythmic practice, but in each case, the effect is relatively the same. An additional differing factor is how each articulation is treated in any given style, even down to the expectations of an individual composer.

The staccato dot (.), which appears either directly above or below a notehead, opposite the stem, originally instructed players to perform the note at half its value, with a rest on the second half. While this interpretation holds true for many styles, there is a fair amount of variation in the meaning of this symbol, even among performances of the same piece. Many performers will tailor their interpretation of staccato in some passages to the acoustics of the room in which they sing or play, as the reverberation times of musical sound can vary greatly in live performance spaces. Other composers had the opportunity to let their desires be known, as in the case of Igor Stravinsky, who generally insisted that his staccato markings indicated that the note was to be played “as short as possible.”

The tenuto symbol (–) is an indication to play a note for full value, but no more, in other words, to let a note take up its entire allotted space, but to also keep it separate from the next note. Like the staccato dot, the tenuto symbol is written either above or below the notehead, opposite the stem. While this symbol may seem redundant, it is highly useful as a clarifying symbol in a complex passage, or in unfamiliar styles. The author, in his role as a composer, advises contemporary composers to use articulation symbols liberally in their music. While most classically-trained performers could supply a reasonably acceptable performance of a piece by Mozart without any written articulations, and indeed frequently do so with the music by Bach, which has few, if any of these symbols, contemporary composers cannot rely on performers’ being able to make these assumptions, and thus should be as specific as possible.

The accent mark (>) always appears above a note, whether the stem is up or down, in order to be somewhat more visible. This mark indicates that a more forceful attack, often in contrast to the tendency of the meter, should be made on that note. The mechanics of this attack vary from instrument to instrument, and among styles, composers and individual performers, but the effect generally results in a more forceful attack at a slightly stronger dynamic level than the surrounding notes.

A cousin of the accent mark is the martellato accent (Λ), which is frequently understood as a combination of the staccato and accent. It is not appropriate in some styles, but is ubiquitous in jazz, where it is often placed above beat-length notes. Experienced jazz brass and woodwind players emphasize not only the attack but the release of notes with this symbol, and often describe the result with the word “daht” in the vernacular (and often highly personal) rhythmic solfege syllables that are used to communicate information about “swung” rhythms.

The notation of rhythm, meter and tempo, whether in the form of individual rhythmic patterns, metric notation, or articulations defining attack and release, is the key to the higher-level organization of notated music. Ironically, it is the aspect of Western notation that came later (although not last), as the music originally notated (Medieval plainchant) was rhythmically formulaic to the point where only pitch and text required notation. Precision of rhythmic notation, and accuracy in reading rhythm, are crucial skills for any musician that will allow the development of true music reading skill. Rhythmic notation can be confusing, and must be read in real-time, but a focus on learning specific rhythmic patterns will yield relatively quick results for most students, and a degree of comfort and familiarity that will allow exploration of a great deal of written music can be developed by regular practice. It is crucial that the goal of an aspiring musician in the Western tradition be to understand musical notation at sight without assistance from a teacher or director. This is the first step toward a firsthand experience of the body of work that is the musical inheritance of a civilization.

[1] This practice has often been imported into writing for wind instruments, where it frequently causes confusion and uncertainty among musicians unfamiliar with its meaning to string players.

[2] This is even the case for music in which the instruments involved do not require use of the breath. This practice allows the music to ebb and flow naturally, and is often accomplished subconsciously by well-trained and tasteful musicians. This tendency is a major difference between the performance of a human player and a machine.