It hasn’t been so many months since I wrote about why I didn’t subscribe to the Cleveland Orchestra this year. With the dismissal of concertmaster William Preucil and principal trombonist Massimo LaRosa, I felt as though I could at least attend a concert with a clearer conscience, however. Hopefully, this is the first step to a more enlightened approach. I look forward to seeing if programming follows personnel in this case. I chose a concert that I would have been sure to pick as a subscriber: composer John Adams conducting his own work and that of Aaron Copland. As I said to my wife when I got home, every piece on the program was a banger, and there was no sense that I was waiting out part of the program to hear what I really wanted to see: an American orchestra performing American music, some of it from the 21st century.

One of my reasons for not subscribing was the customer service experience, and I was somewhat hesitant to buy a ticket given the iffy weather last week–I did not want a repeat of last winter’s having to forego Mahler’s Ninth symphony despite having the ticket in hand. So I put off buying until the day before the concert. The Friday night performance, unlike some Fridays, included the entire program, except for the pre-concert talk, which was not made clear on the website. I also had trouble using the website to purchase my ticket–I could not remember my password, and wasn’t able to reset the password once I had been emailed the code. I am very much in the database there–I actually received four copies of the email promoting this concert. A phone call to the box office solved the problem, however.

So–thinking I would hear the talk, I arrived an hour early, and once I found out there wasn’t to be one, I resigned myself to killing an hour until I ran into Mike Leone, who I know from my time at Ohio State, and who played trombone in the Lakeland Civic Orchestra for a time. We reconnected, and it was time well spent in the end.

The concert itself, then. Buying my ticket late, I did not have my pick of seating locations, but I was able to find a seat that was very well-priced, and actually well-situated. In particular, while I wasn’t any closer than I often have been, I feel like I could see and, more importantly, hear very well, and I will be looking for seats in this location in the future.

A side note: this is not my first time at Severance Hall this fall. On October 30, I took my family to see the United States Marine Corps Band, another world-class ensemble. It was, of course, fantastic. As seating was first-come, first-served, we found seats in the Dress Circle, and the experience was very good.

The concert opened with John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Of Adams’ works, this is likely the most familiar, and with good reason. In fact, it is one of the pieces I emphasize in my music appreciation classes. The playing was exactly what the piece requires–precise, forceful, and on top of the beat in a way that I don’t always hear from the Cleveland Orchestra. Adams’ conducting is perhaps more suited to band than orchestra: mostly small beat patterns and a very literal approach to the stick. For Short Ride, it is appropriate, however, and it got what was needed from the musicians. Interestingly enough, after 30 years, Adams still conducts from the score for this piece (and all the others on the program). It gives this conductor-turned-composer-turned-conductor some hope. While I came to see Appalachian Spring and Leila Josefowicz, the curtain-raiser sticks firmly in my mind from last night’s program as the standout moment, perhaps because I knew immediately that I had returned on the right night.

Then to the music of Aaron Copland, and an incredible performance of Quiet City. This may be the Copland piece best suited to the Cleveland Orchestra, as it showcases this group’s incomparable string section and two of its strongest wind players–principal trumpet Michael Sachs and English hornist Robert Walters. The performance was impeccable, and, unsurprisingly, the strings seem to have adapted to the reality of acting concertmaster Peter Otto, who leads the section with confidence.

Appalachian Spring has long been one of my favorite pieces of music. For a time when I was young, it seemed like every group I was in performed the Variations on a Shaker Melody in either its band or orchestra version, but when I played the full 1945 suite in youth orchestra, it was a revelation. I normally study scores in advance of attending a Cleveland Orchestra concert, and I have the score to Appalachian Spring on my shelf, but it wasn’t really necessary in this case, although there are some things I am going to go back and look at when I get the chance.

One of my favorite Cleveland Orchestra concerts of the last few years was Marin Alsop’s rendition of Copland’s Third Symphony, so I knew that the orchestra was more than capable of presenting an inspiring performance of middle-period Copland (that said–wouldn’t it be great to hear Connotations or Dybbuk Severance? Just a thought…). This is a much tougher piece to lead than either of the two previous pieces, and Adams seemed somewhat less comfortable with it–I would be, too. He conducts mostly from the wrist and elbow, letting the stick do the bulk of the work, and saving the shoulder for bigger moments, which is similar to my approach, but this may limit his expression. I also saw more knee-work from him than I am comfortable with–since musicians can’t see your knees, for the most part, bending them isn’t particularly helpful, and can actually obscure what is happening with your upper body as you bob around in their peripheral vision.

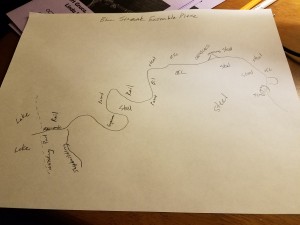

The Orchestra, of course, takes all of this in stride, having played the piece many times. There was a tiny flub in the trumpet section, a rarity at Severance, and it was fascinating to see that lead the orchestra to sit up and take notice–tighten up in the way that the best musicians do in such situations. Overall, Adams’ interpretation was fairly strong, if not really ever unorthodox, and the musicians bought into it. While I have played Appalachian Spring and the Variations, I believe this is my first time hearing it from the audience, and it does not disappoint. I realize, now, how it truly is a suite of the ballet–it is very modular in its construction, shifting from one episode to another relatively quickly. As luck would have it, I am just completing the first draft of a piece, Channels, for the Blue Streak Ensemble, that is constructed more or less the same way, and I have been worried about whether it will convey a sense of unity. Copland here demonstrates that unity can arise from the sorts of rhythmic and melodic and stylistic variety that one finds in Appalachian Spring, and it is a balm to this composer with a looming deadline!

After the break came Adams’ own work again, his latest violin concerto Scheherazade.2, performed by its dedicatee Leila Josefowicz. I first saw Ms. Josefowicz perform when we were both teenagers–I in the audience and she onstage with the Columbus Symphony playing the Tchaikovsky. That vogue for very young violinists seems to have passed–and that whole generation (Josefowicz, Sarah Chang, Joshua Bell) has gone on to show that our excitement over them was not unfounded. Josefowicz did not disappoint in the slightest, although Adams’ orchestration at times threatened to overpower her–this is suprising after reading his thoughts on his experience with his first Violin Concerto in the late 1980s in his memoir Hallelujah Junction. In his remarks from the podium, Adams admitted that his first experience with Scheherazade is Rimsky-Korsakov’s tone poem of the same name which, ironically, would have demonstrated a more careful approach to balance between solo violin and a large orchestra.

This is an interesting piece at this moment, and Adams admitted to this as well. I consider myself an ally to feminism, and it is clear that Adams does, too. Yet, is he the one who should be writing this piece? Aren’t there enough examples of men telling women’s stories? The other component of this work is its attempt to deal with male violence against women, and this is certainly a poignant moment for the Cleveland Orchestra to present such a piece, coming less than a month after the ouster of two misogynist members. In the notes, Adams states that the work is a “true collaboration” between himself and Josefowicz, and I would be curious to see how that collaboration unfolded. (Copland, of course, worked very closely with choreographer Martha Graham in creating Appalachian Spring, with Graham going so far as to suggest specific rhythmic ideas as well as the scenario–perhaps this is the reason Adams programmed the pieces together).

That said, I will be giving Scheherazade.2 more listening and score study. It is a kaleidoscope of orchestral effects and in juxtaposition with Short Ride in a Fast Machine, one sees just how far Adams’ style has progressed over the three decades since he came to prominence. One misses, at times, the organic, unified approach to a composition that his more minimalist-inflected work brought, but this is truly a different language, and Adams has long insisted that he never meant to be a minimalist. The cimbalom adds an interesting tonal element to the work as well, providing a link between the harp and the rack of tuned gongs in the percussion section. What I heard was good, but as the only work on this concert that was unfamiliar to me, I will have to return to it. With Josefowicz having performed the piece 50 times in three years, it hopefully is finding a permanent place in the repertoire.

And so I returned to the Cleveland Orchestra, as was inevitable. It felt right, and I felt the joy I always hope to feel when I go, that I should always feel when I go. I felt both comforted and challenged, and I felt like the musicians had something important to say about the music they were making. In all, it was time and money well-spent, and if it is professional development, I feel that I grew as a musician last night.