This post is one of a series explaining and exploring the process and documenting the premiere of my Symphony in G, “Doxology.” My influences have been many and wide-ranging, so there will be two posts about them.

No creative work springs ex nihilo from a human mind, and for thirty-odd years, since my days exploring classical music four CDs at a time from the public library, I have been thinking about the genre of the symphony, listening to its most famous examples (and some less-famous), talking about it with people interested and not, and pondering what my contribution to the genre might be.

To say that I, like Newton, have stood on the shoulders of giants is an understatement, and while this new work is in many ways the finest I have been able to make in the times and circumstances I have lived, there are also many works that it fails to compare to. I don’t know that I can say that this is a work, or that I am a composer, that pushes the art form forward: it pushes my art forward in important ways, but I don’t expect to be included in future music appreciation courses.

Nonetheless, the symphonist must decide just what a symphony is, and what it means to write one. My solution is certainly not the only answer, or necessarily a correct answer in everyone’s eyes. It is, of course, shaped by my decades of listening, analysis, and conducting, and often by the music that I considered during the six years my symphony was a work-in-progress.

What follows, then, is a shortlist of symphonies–and symphonists–that were in my mind before and during those years. The creative DNA of my symphony can be found in these works.

Brahms

The four symphonies of Johannes Brahms loom large over any latter-day symphonist, or should. In the early days of this blog, I spent eighteen months working through Mahler’s nine numbered symphonies, and while I learned a great deal from the experience, Brahms’ works have been and remain more foundational. As sprawling and wonderful as Mahler’s works are, they aren’t on this list of significant influences, and I will have to think more about why that is: I suspect it is because of their deeply personal language that demands public expression of what for me is a more private experience.

Brahms’ First Symphony was one of the first symphonies that I played, with Peter Wilson and the Columbus Symphony Youth Orchestra. The trombone part is crucial, but limited to the final movement, but even so, I relished exploring this work–when we began it, I hadn’t even realized that Brahms wrote symphonies, only that he was The Lullaby Guy. I’ve always felt a kinship with Brahms’ process of this piece, which gestated over a long time–decades–as the composer worried about how he would stack up to what came before.

In preparation for that youth orchestra audition, I purchased a CD reissue of George Szell’s 1966 recording of Brahms’ First with the Cleveland Orchestra. I first heard it live in 1993 in Youth Orchestra rehearsal and the same year as an audience member at a concert of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra: I remember Alessandro Sicilliani’s shockingly fast opening tempo in the first movement, which was unconventional, but I rather liked it.

Later, Brahms’ Second Symphony was the audition repertoire for my first year of college, and I discovered its finale, one of my favorite symphonic movements. The Third and Fourth are just as wonderful in their own ways, as well. I often tell my music appreciation students to take a rainy afternoon and listen to all four Brahms symphonies and know that they will have spent their time wisely.

Beethoven

Like Brahms, I too have had to consider the legacy of Beethoven as I have considered the symphony. As a trombonist, I’m sidelined from six of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, but as a conductor, I have been able to lead the Lakeland Civic Orchestra in four of them: the Fifth, Eighth, First, and Second. I’m not completely sure which of the bunch I heard first in performance–I think it was probably the Fourth and the Seventh with the Dresden Staatskapelle, on tour in Columbus under Giuseppe Sinopoli in 1993 or 1994. By that point, I had become obsessed with Toscanini’s renderings of the cycle with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which to this day are my go-to recordings, in the rerelease by RCA Victor on CD. I remember a few weeks in the winter of my first year of college when I would slip up to my dorm room after lunch for a daily dose of Beethoven. I would put one of those five CDs in my player and hear a movement or so.

My symphony, of course, takes the four-movement plan that Beethoven (mostly) followed. He didn’t invent that plan, but the influence of his works makes anything else seem a little bit suspect (although the symphony-in-one-movement has enormous appeal for me as well). Like Brahms, the centrality of motivic development–and the ability to leave that technique aside at times–is important in my work. I often turn to George Grove’s book on Beethoven’s symphonies, and I remember my first reading of it realizing that Beethoven’s obsession with fugato technique was perhaps not to my liking: I once used it quite a bit in my work, but it came to seem obvious.

And then there’s that First Symphony, the harbinger of great things to come. Grove points out that, while it is good enough, if it were from the pen of a composer who didn’t go on to bigger and better things, it would be completely forgotten. We only know it because it’s by Beethoven. But in 2006, when I was thirty, I made one of my more serious abortive attempts at writing a symphony because that’s how old Beethoven was when he wrote his first–I figured it might be time, but, of course, it wasn’t.

Aaron Copland: Symphony No. 3

On the day I finished creating the instrumental parts for my symphony, July 4, 2025, Becky and I got in the car to pick up Noah and Melia from church camp. The local classical radio station, WCLV, was playing American music as befit the day, and the second movement of Aaron Copland’s Third Symphony came on. I said to Becky that this was music that I had considered a “mark to beat” as I composed, and if any one composition deserves that distinction, it is this. My professional bio for a long time said that I wanted to compose the Great American Symphony, but with his Third, Copland beat me to it by seventy-five years. The recording you’ll find in my collection is on a 1996 Chandos disc featuring Neeme Jarvi leading the Detroit Symphony Orchestra–an ensemble that looms large in my understanding of the symphony. I first heard the piece live in a 2013 performance by Marin Alsop with the Cleveland Orchestra. Copland’s Third is broad, accessible, and unapologetic. It articulates and sums up, to me, much of what audiences have come to love about its composer’s music: lyricism, thrilling scoring, rhythmic vitality. I admire the work’s honesty and its direct appeal. As I wrote a piece about faith, based on a call to praise that is also a statement of faith, Copland’s Third stood as a model for the kind of community truth-telling and celebration that the Doxology also represents. The Fanfare for the Common Man, the basis for the fourth movement of Copland’s piece, appears in a guise and fashion that in some ways supersedes the original–although that piece has been a personal touchstone longer than I have been interested in the form of the symphony as well. My own quotation of Old Hundredth in the fourth movement of my symphony, while different in execution, is inspired by Copland’s self-quotation.

Andrzej Panufnik: Sinfonia Votiva (Symphony No. 8)

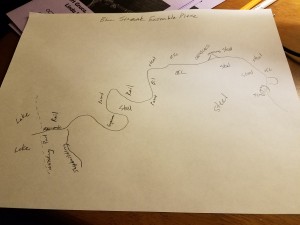

Back when I was an avid purchaser of CDs through the mail via the BMG Record Club, a recording of Roger Sessions’ Concerto for Orchestra caught my eye, and on the same disc was this symphony by a Polish composer I had never heard of. I can’t say that I was particularly struck by the music or that it became something I listened to regularly, or that I was inspired to listen to the rest of Panufnik’s oeuvre. But something that did stick with me was the diagram plotting out the entire structure of the 22-minute work, included in the liner notes (and pictured in the video linked above). I was a graduate student in composition at the time, and I was struggling with how to develop larger forms. As tempting as it was to sit down at the computer and begin putting notes in to the score, I was coming to see that, as with writing words, pre-writing is an essential part of composition. Fifteen and twenty years later, I would develop my own diagrams for my Symphony in G, and take a single page–in this case, an existing hymn–as my overarching structure.

The result is, I think, as with Panufnik, a work that balances expression with structure, which is something that I find particularly symphonic. While some composers aspire to formal or structural freedom, and many listeners claim to relish it, the truth is that the vast majority of successful works are built around relatively simple approaches and structures. I’ve referred elsewhere in this blog to my favor for Nico Muhly’s “one-page sketch” for a work, and now I realize that Panufnik’s work led me to this idea several years earlier than Muhly’s music even appeared on my radar (I completed graduate school around the time Muhly started to develop an international reputation).

I’m also intrigued that the Boston Symphony Orchestra commissioned this work for its centennial in 1982. I’ve always had an interest in these big anniversary celebrations, both because I was born in the midst of one (the United States Bicentennial) and, musically, because I attended the premieres of many of the fanfares written for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra for their centennial in 1994-1995. I love the idea of marking these milestones, especially with music. I wrote my own piece, The Lovely Soul of Lakeland, for the Lakeland Civic Orchestra to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the founding of our sponsoring institution, Lakeland Community College in 2017, and I can only hope that I will be around for the 100th birthday of the Lakeland Civic Orchestra in the late 2030s.

Alan Hovhaness: Symphony No. 2, Op. 132, “Mysterious Mountain”

I first encountered the music of Alan Hovhaness driving myself home from high school one afternoon, when WOSU (89.7FM) would usually play a symphonic work during the 3pm hour. The choice that day was Hovhaness’ Symphony No. 50, “Mt. St. Helens,” and as I drove, the still, quiet second movement, describing Spirit Lake before the eruption gave way to the final movement, “Volcano,” with its two sharp bass drum strokes exploding into chaos. I was fascinated by the topic of this symphony: although I was young, I was fascinated by the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens that inspired Hovhaness when it happened, which led to my parents subscribing to National Geographic, whose 1981 issue with the volcano on the cover I thoroughly wore out. This was the 1993 recording by Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony.

I explored Hovhaness and his music more deeply through the 1990s and into the 2000s. In college, I studied his Symphony No. 4, written for winds, and looked into his other band music while also keeping an eye out for those elusive recordings–there are many released originally on LP that hadn’t been re-released on CD, and many works that have never been recorded at all from this prolific composer. When I was a high school band director, I programmed The Prayer of St. Gregory the year Hovhaness died, 2000. My first suite for string orchestra was an homage to three composers whose music was an inspiration to me in my early years: in between movements celebrating Philip Glass and Jean Sibelius is a Meditation in Memoriam Maestro Hovhaness. I haven’t had a chance to return to his music as a conductor, but if I did, it would likely be his Symphony No. 2.

I first heard “Mysterious Mountain” in the 1990s, on a concert with the Cincinnati Symphony. It didn’t make the same immediate impression that “Mt. St. Helens” made–it’s just a different kind of piece, and really, more in line with the composer’s personality. On repeated listening, my esteem for the work grew, and I now think it one of the finest American symphonies. I admire its sincerity, its craft, and its succinctness.

There is the first group of my symphonic influences. Look for a second post shortly, along with more updates on the rehearsal process in the run-up to the premiere of my Symphony in G, “Doxology” with the Lakeland Civic Orchestra on Sunday, November 9 at Lakeland Community College in Kirtland, Ohio. Information and tickets here.