I’ve been digging further into the Cuyahoga River and the 1969 fire that spurred the nascent environmental movement in preparation for my new piece for the Blue Streak Ensemble. Part of the difficulty is separating myth from reality, Randy Newman songs and Mark Weingartner novels aside.

I’ve become fascinated, or remain fascinated, with the way that the river has been changed into a man-made object rather than a natural feature, at least for its last six miles. An amazing app of Cleveland Historic Maps has helped with this, as I have pinpointed the location of the fire, mapped it onto my own experience of the river over the last six-and-a-half years living near it, and begun to consider a shape for this piece. I’m amazed at how much industrial plant that was present in 1951, the year of a USGS aerial survey, is simply gone, leaving either scars or having been redeveloped. I’ve have read and heard about the decline of heavy industry in Cleveland, but to look at how it was crammed into the river valley in the 1920s and see the shape of the same places nearly a century later drives it home.

The scale of the places is just as daunting–plants that employed tens of thousands of workers at their peak could surely ruin a river, and a lake. Little wonder that such places symbolized optimism and progress for the mid-century mind in the ways that they dwarfed their inhabitants.

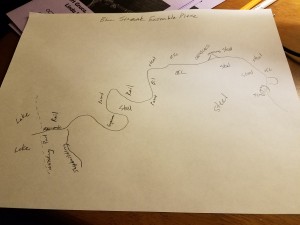

I’ve also taken a page from Nico Muhly, who describes in a recent article his compositional approach. While my experience of being a composer is lived quite differently than his (I have no doubt that he won’t ever be looking to my writing or music for inspiration), I’m taking his idea of a one phrase synopsis and a one-page birds-eye view map of the piece quite seriously. My map is going to be based on a tracing of the shipping channel of the river–the lowest six miles that pass through Cleveland and that have be reshaped for the economic purposes of our species.

Little wonder that by 1969 the river was lifeless, a murky, roiling soup of human and industrial waste–it was not allowed to be itself, from the 1820s when its mouth was recut to eliminate its final bend before draining into the lake, to the addition of steel-walls to fix the location of its banks, and straighten its meanders.

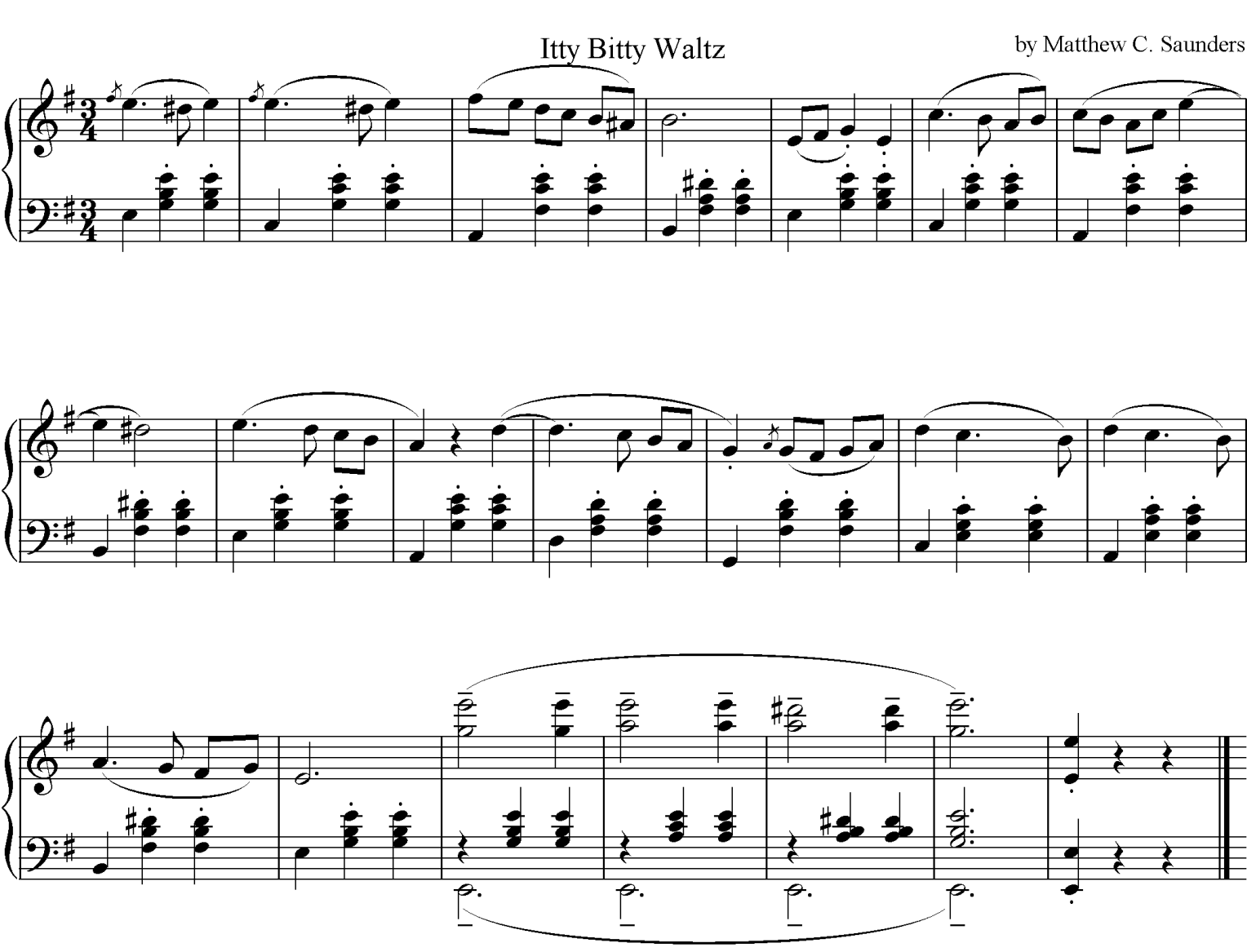

How to express all this musically? This is the problem. I created a little sketch the other day–a mixed-meter passage that I could imagine opening the work, but I wasn’t satisfied with it, and I realized I wasn’t ready to put down notes yet, but I will need to be ready one day soon. I still want to see the valley, the mounds of slag and ore and limestone; the enormous plants; the scene of the crime of this fire. I was hoping for a river cruise, but I have missed that window for 2018–the tourist boats have finished for the season, and it is this moment when one needs Friends With Boats, I suppose. I spent some time on the river vicariously this morning watching video taken from lakers going to or from Lake Erie up the river to ArcelorMittal Steel, the path I would like to take, and that may have to do for now. Tomorrow, however, I will be taking Noah and Melia either to the zoo (if the weather is fair) or the natural history museum (if not). We make take some time to attempt to drive some of these areas as well, and soon, very soon, it must be notes.