Yet another post in response to a question from my student Cooper Wood, who sent a text message yesterday asking, in part, how I work with harmony, and how I structure chords. Early on in my lessons at Ohio State, Donald Harris put a similar question to me, and I don’t quite remember my answer–I’m not sure that I was able to answer him at that point, so here, twelve years later, is an attempt.

I have often thought of composers falling into three groups–harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic. Beethoven and I are rhythmic composers, and for us, if the rhythm is correct, the harmony and melody will fall into place around it through the application of motivic constructions and a sense of when the harmony needs to change. It is not that a rhythmic composer ignores harmony but that the musical meaning isn’t concentrated there. As interesting as Beethoven’s harmonic language can be, there is no equivalent to the Tristan chord in his work.

Two things I don’t do, at least not regularly: I don’t consider my work from a functional/tonal perspective, at least not during the writing of it, and I don’t simply sit at the piano and let my fingers fall where they may, to see what kinds of chords come out. That is to say, I rarely think of chords in either sense–neither as units functioning in some system nor as groups of notes played simultaneously.

Here, then, are some of the ways that I think about harmony:

Thickness of texture: Is this a moment in the piece where a more complex, richer sound is required? This makes harmony into a timbral decision, where there is a continuum, something like this:

Single line—Octave doubling—Non-octave doubling—Two or more parallel intervals—Voice-leading—Clusters

My 2010 Piano Sonata displays almost all of these at some point.

Scale and Mode: While I rarely explicitly choose a specific scale or mode, melodically, my music often behaves in modal ways, and I feel that introducing an accidental is a change in harmony. On the small scale, this may happen quickly. I notice a distinct preference in my music for flats over sharps, and my feeling about accidentals is that they point, so I am frequently choosing notes that point down a half-step. My trombone concerto Homo sapiens trombonensis (2005) includes examples of this sort of thinking.

Consonance and Dissonance: I spent several years before graduate school trying to come to terms with my personal approach to dissonance, as nothing, at least to my thinking at the time, says more about a composer than his or her use of harmonic language. I still hold to Vincent Persichetti’s idea, laid out in Twentieth-Century Harmony, that the degree of dissonance is something that a composer must tightly control. So, in my work, I tend to make harmonic decisions based on how consonant or dissonant a passage needs to be, adding notes when appropriate, and thinning out the texture when necessary. For me, chord constructive is an additive conception.

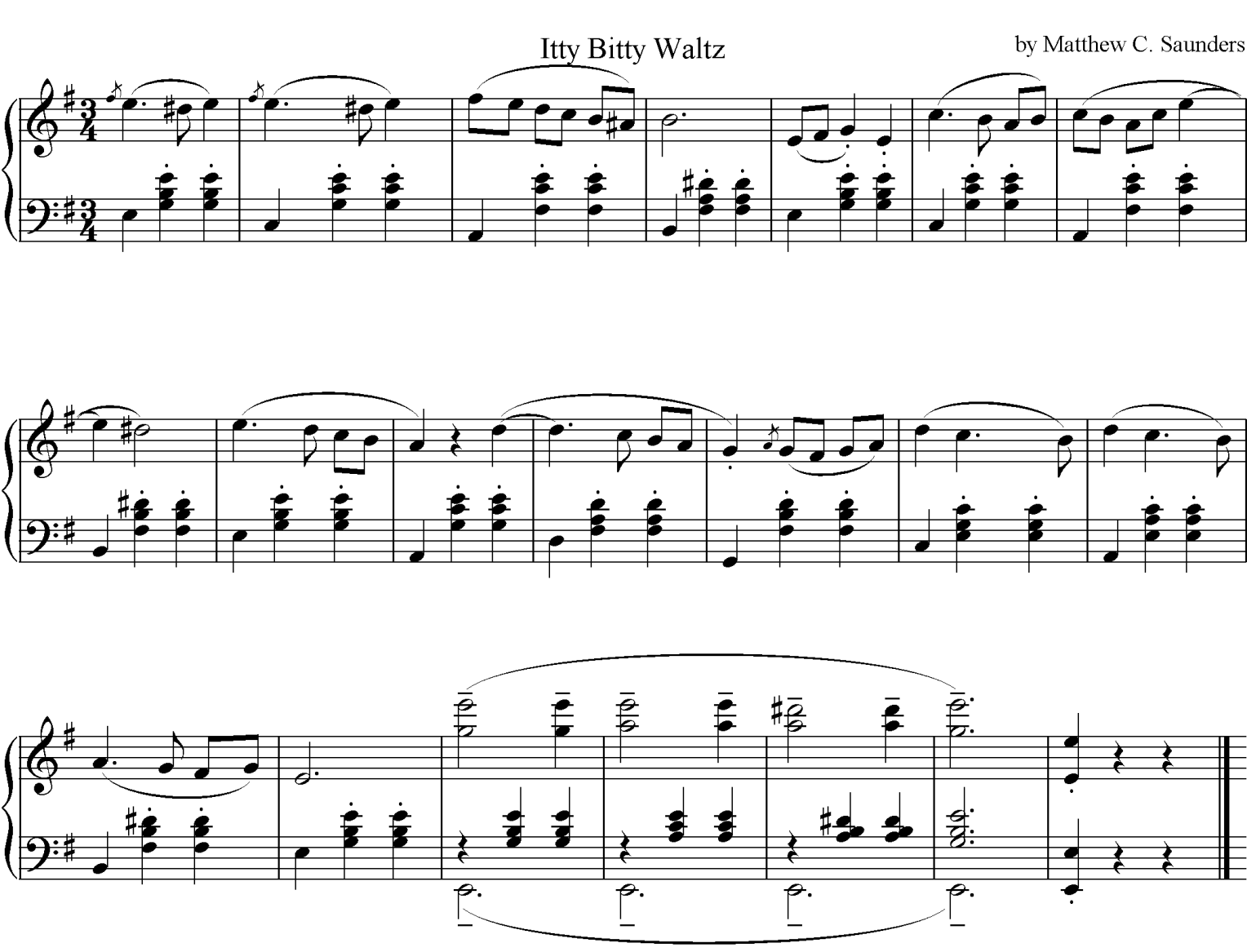

Organum: William Russo’s book Composing Music was at one time a standard title on the shelves at Barnes & Noble, and though I never bought the book, I certainly read large chunks in comfortable chairs. One idea that stuck with me is what he calls organum–doubling a line at a parallel interval to increase the complexity of the timbre. A key feature of my style for at least the past ten years has been melodic doubling in sevenths, usually minor sevenths, although sometimes following the diatonic scale. Much of my piano music uses these parallel sevenths, beginning with 2008’s Starry Wanderers.

Set Class: In some of my works, I have, early on in the process, discovered a set that appeals to me, and based the work on that to one degree or another. This is usually an outgrowth of my work with motive, and in some ways, the set becomes a harmonic motive. In my most recent work for solo piano, The Rainbow’s Daughter, I found myself drawn to the set [0236] during the composing of the first movement, “Polychrome’s Prism.” Its two thirds (which I wrote as two sixths) slide easily into a minor triad, giving the sense of refraction that I wanted to suggest. In the subsequent movements, I found that I could turn [0236] just as easily into an augmented, diminished, or major triad, and the structure of what is one of my most harmonically-conceived pieces became clear.

Counterpoint: I often attempt to combine melodies, resulting in harmonic structures. My training in 16th-century counterpoint (begun with Dan Trueman in music theory at CCM, and continued in self-study, most significantly in Schubert’s Modal Counterpoint: Renaissance Style, which I used as a teaching text) and in 18th-century counterpoint (with Jan Radzynski at Ohio State), had the desired effect–it gave me a sense of the possibilities of the ars combinatoria and as a result, I think about the direction of each voice in a composition, with the resulting variety of rhythmic and melodic direction. I don’t, however, generally include canon, fugato, or strictly fugal sections in my work. I don’t find that these techniques provide sufficient reward for the effort involved.

Layering: In place of imitative counterpoint, I often choose a layered approach, in which small, repeated melodic/rhythmic units either build a texture through successive entrances or appear simultaneously. I used this extensively in my 2010 band piece Moriarty’s Necktie, and the idea of adding a layer is never far from my mind, although this rarely results in a simple melody+figuration texture.

So–I don’t know that I have answered the question put to me now by both my teacher and my student, but these are some of the things that I think about as I work. For Cooper, I hope this helps. For Don, just know that I am still working on that answer for you.