They are tearing down my high school–Upper Arlington High School–over the summer, so I went back last month, and I took Noah, one day shy of turning 11, with me, to a walk-through day sponsored by the alumni association. It was the first time I had been back to most of the facility since I graduated, although I had been to the music area and the auditorium a couple times, mostly associated with the 2008 premiere of the piece I wrote for the band to commemorate the career of my high school band director, John Blevins.

I was surprised how much was the same. The building had not undergone any major renovations since before my time there, and even some of the fixtures were memorable. The light was the same—too little. The halls were surprisingly at once bigger or smaller than I remembered, and some doors seemed to be labelled with their original markings from the 1950s. It was a good day to be there, as the building was still very much in use, the final packing up for the summer still to come. In fact, there were signs asking us to stay out of classrooms. When I came to the band room, though, I couldn’t help myself, and Noah was shocked when I stepped over the caution tape to walk through the rehearsal space one last time, peeking at the locker that I had shared with Jay Moore during our junior and senior years, and snapping a couple of photos. Crossing lines put in place by authority is not something my son is accustomed to seeing me do, but I assured him that it would be alright, even while also telling him not to get any ideas.

Overall, I had a good four years in high school, from 1990 to 1994. I excelled academically, found my place in several groups of my classmates (band, mostly, but also the honors students, the gifted program, briefly the drama club, and too late the quiz team), and discovered the passion that would lead to my career. I wasn’t bullied, and I don’t think I was a bully, but neither was I a standout in the social world of my high school. My family lived a comfortable life, but I was surrounded by people whose parents were wealthier than us: lots of my friends were given a car when they turned sixteen, but I was given a set of keys to the family car.

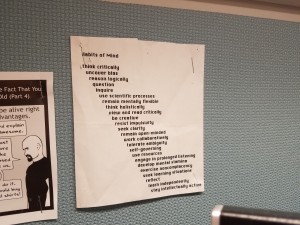

What I am amazed by, these years later, is the quality of my teachers, especially after spending more than twenty years trying to be a teacher myself. I wrote once of the importance of every teenager having a role model who isn’t their parents—an uncle, spiritual guide, or teacher—and Upper Arlington High School had an embarrassment of riches among its faculty. If I hadn’t found that person in Mr. Blevins, there were easily three or four other teachers each year who could have been that person, and frequently were for my classmates. Even students who didn’t seem to fit could—and did—find these people. The huge number of clubs and sports coached by teachers meant that there were plenty of chances to interact with them in less-formal ways than in the classroom.

Upper Arlington High School was—and is—a well-funded school, attended by students who had all the advantages that wealth brings, and I’ve truthfully struggled my entire life to reconcile that experience with what I have seen and heard elsewhere, as a teacher, as a college professor, and as I’ve listened to the experiences of others in high school. In a negative sense, I have come to see what I often felt as entitlement, and white privilege, and I am frustrated that we can’t find a way to give what I had—and took for granted—to all kids.

Some things I would have done differently. Coming into high school, I had a pretty good network of friends, and leaving it, I had at least one close friend, but I don’t think I engaged in building relationships as much as I could have, and I didn’t manage to maintain those relationships in any kind of real way after graduation. On graduation day, I went home with my parents, and didn’t have any plans with the people I had just spent four years with. My father told me to go seemy friends, but I didn’t have anywhere to go: all my friendships but one were essentially situational, and when high school ended, they basically did, too. This was in part what I wanted—I was very ready to go on to the next thing and start living my life, and I viewed going away to college and leaving everything I knew mostly behind as a big part of that. It wasn’t until I got onto social media (nearly 15 years later) that I found out what happened to most people. Mistakenly, I had thought that the only important part of high school was high school.

I have also come to realize that for many of my classmates and peers at high schools of all types, the high school experience was not a good one. For a place that should be dedicated to learning and knowledge, too often there is very little of either. There are those who placed their trust one or another teacher, only to have that trust betrayed in often horrifying ways. There are people who were bullied, or ostracized, and they carry the damage with them into their adult lives—adulthood is high school with money, as the saying goes. There were people who simply had to wait and endure that four years in order to be able to go and pursue their visions, goals, and dreams in a way that didn’t fit in with a bell schedule, semesters, homework, and hall passes, and resented it. There were people who injured themselves in lifelong ways, either on the athletic field or otherwise, trying to come up to what was expected of them. As Hesse suggests, education is a way of placing us beneath the wheel; the Bildungsroman is almost always written while wearing rose-colored glasses.

As my children approach this world—Noah is headed into the minefield of middle school in the fall—I try to see what I want for them. The high school they will attend is most certainly not Upper Arlington in 1994, and I would like to see them aim higher than most of that school’s students who I seem to meet. I realize now that I am a very different person because of the people I was around in high school—the artists, musicians, and honors students. It was nothing in the water—it was constantly being around people whose parents shared the same goals as me. I want my children to be able to assume that they can use their minds to earn a living, to be able to provide a good life for their children, to not be afraid of books or art or people who are different (although there was plenty of that at Upper Arlington, too). I want them to know success, and to know a world where they believe success is possible, and where people are willing to at least give them a chance to succeed.

Twenty-seven years out of high school, I am still thinking about high school. As the physical evidence of the school is being torn down and replaced with something new, what happened to me in those four years—good, bad, indifferent—carries on, more than a look through old yearbooks (I am shocked at how many strangers stare back at me from those pages), or posts on social media, or the reunions that I’ve never been to.

I never wanted to be a nostalgic person, and I detest the kind of nostalgia that sees the past as better. I refuse to engage in golden age thinking (or gold-and-black age thinking, in this case). But the Greek roots of nostalgia refer to pain—pain for one’s home. There is a part of me that does ache for that time—to put on the band uniform, or learn fresh some way that the world works, or for once feel like I am meeting the world’s expectations. I shouldn’t, because that was all an illusion, and it was all designed for someone else. I wouldn’t go back—most days—but walking through that doomed building reminded me of what a time it was, and how it continues to make me who I am today.