I don’t know what the worst part about being a composer is (probably the rejection), but many of my colleagues feel that making parts out of a large-ensemble score is just about the worst. I disagree: with a change in attitude and correct workflow in your notation software, extracting parts doesn’t have to extract its pound of flesh, and it can even be joyful.

Joyful? you say. How can something that is just mechanical drudgery, a chore to be completed after the long slog of creating a score that looks halfway decent–essentially the creation of twenty to forty more little scores–how can that be joyful?

My answer lies in outlook: what is it that we are really doing when we create parts?

For me, the music I create is for people: for the people who will perform it, and for the people who will hear it. I don’t write it so that I can print a beautiful score, sit it on the shelf, and put the MIDI playback on while I sip a beverage. The music needs to go out there, mingle with performers and audiences, and in so doing allow all of us to have a conversation about something. Perhaps, as Libby Larsen says, about what it means to be alive (if I have done my job).

It can’t get out there without the parts. A score is great for the conductor, but we can’t hear it without the parts. Theorists and musicologists and other composers need the score, but for a performance to happen, we need parts (unless there is going to be a page turner for every musicianon stage).

When you are making parts, you are creating the material that will allow your music to come to life. You are creating the thing that will ultimately allow someone to bring your music to life. This isn’t a chore: this is the final link in the chain, and the musicians in the ensemble are honoring you by spending time with the parts you create. You need to honor their time and effort by giving them material that is clear and easy to work with. There is no music without the parts that you are about to create.

That’s the philosophy. Now, how do we manage workflow to make part extraction less painful? (I use Sibelius v. 6, so ymmv).

The approach I’ve found is that you actually do what composers started out doing at the dawn of polyphonic music: you start out by writing the parts. This doesn’t mean some Percy Grainger setup where you write thirty parts on thirty different pieces of paper, but it really isn’t far off.

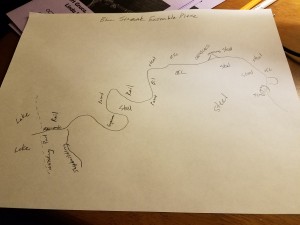

I start with a short score (a debatable practice as I discovered recently on Twitter) as my first computerized step (these days, I do a fair amount of sketching at the piano with pencil and paper first). If I’m writing a band score, one staff for each instrument or even family: there will be three b-flat clarinet parts eventually, for example, but for right now they all go on one staff, if I’m writing a band piece. If it gets very polyphonic within the section, I may jump over another staff and make a note to myself. It’s still a sketch, after all.

The next step is crucial, and it’s something that honestly took me far too long to figure out. For many years, I left dynamics and articulations to the end phase of the process, but as I’m more comfortable and mature as a composer, I am more confident deciding on these factors earlier on. The result is this: there is quite a bit of copy-and-paste in the next couple steps, so why not copy and paste all of those dynamics and articulations right along with the notes?

Having fleshed in the short score to the degree possible, and decided that I have essentially written the piece, it is time to create the parts. In Sibelius, I create a new instrument for every part I intend to have in the final version. Each instrument gets its own staff. This is crucial. Then, I copy and paste from my short score staves into the new instruments. The result is what I call my “ultrafull” score, but it really is all the parts, with one exception: every percussion instrument gets its own staff at this point.

I will admit to being less than confident as a percussion writer. You would think, that a few decades as a trombonist sitting in front of the percussion section, or as a conductor dealing with all manner of scores and solutions to printing parts for the percussion section, I would have a little better idea. The truth is that for some reason, I am intimidated by writing for percussion the same way that I am for guitar, or organ, or accordion. Other composers may be able to think of percussion much more integrally then I do, but it seems like I always get to the end of the sketching phase, and discover that I have bars and bars of rest for the percussion section, when they should be playing a much more active role.

The ultrafull score then, is the place where I rectify my percussion writing with reality. I hope that I have by this point determined just how many percussionists are available to me, and what instruments the commissioning group has in their closet. If not, it’s time for that conversation. On my most recent band composition, I had to spend some time whittling 6 percussion parts down to 5 after the director had a slight shortfall in the back row. Once I have exploded my short score to ultrafull, I have all the parts, since the next step is to render all the individual percussion instruments into the appropriate number of parts, playable by one musician each. I strongly recommend making a chart with color coding for each percussionist so that you can think about how long it takes to change instruments, and just how much work everyone in the section will have.

The next step, once I have my “score of parts” is to reduce parts onto the staves that I want to appear in the score. In Sibelius, I am going to keep all of my single instrument staves. Some of them will appear in the score, for example, there is usually only one piccolo part. If there are the typical two flute parts however, I will create a new flute instrument that will show both parts and will end up in the conductor’s score. I have to be pretty sure that I don’t want to make many changes at this point, and if I do, I need to make sure that I change both the single player staves and the full section staff, but Sibelius’ Arrange function makes it fairly quick to get more than one part on a staff. By paying close attention to where there are unisons, rhythmic unisons, or multi-rhythmic moments, I can work through the part fairly quickly, with a minimum of error. As the Arrange dialog box always suggests, it’s best not to try more than a few measures at a time. This is also the moment, when I add a2, divisi, or similar markings.

I will typically mute these combined scores in the Mixer window, so that my single instrument staves are the ones I hear on playback. This eliminates some of the clunkiness that happens when too many instruments are on the same note. Truth be told, I am still using Sibelius Sounds as it came out of the box, partly because I am a cheapskate and all of my equipment is old, and partly because of my maxim that if you can make it sound passably good in MIDI, there is an outside chance that it might sound good with human players. If I were better at audio, I might have a different approach here.

With the score staves muted, then, the next step is somewhat ironic. To make my full score, I now hide all the staves that are actually playing back, i.e., the staves that will be my parts. (I typically do this using Focus on Staves in Sibelius.) The staves you hear are not the ones you see, and the staves you see are not the ones you hear! This means, that if say, 1st and 2nd clarinets are playing the same music, you hear two clarinets in the playback. Again, I don’t put a lot of stock in MIDI playback, but it’s an old habit that dies hard.

With the score finalized, that is, with the score staves visible and the part staves hidden, it is time to turn to the parts. I found an old score recently that I had created in Sibelius v2, and my score was in a folder with a bunch of other scores that represented the extracted parts. I know that I am not the only person whose workflow was revolutionized by the Dynamic Parts function of Sibelius, and to this day it is one of my favorite features of the program. It means that when it is time to create parts, all of my parts are right there with dynamics, with articulations, and basically ready to go. Remembering to set as many things in the Parts menu that will apply to everything as possible, it is just a matter of opening the part, checking the layout, making sure that page turns are sensible, finding those collisions that always sneak in, and creating a PDF.

I don’t want this post to sound too much like an advertisement for Sibelius, and I can’t really speak to Finale, which I haven’t used in 15 years, or Dorico, which I have never used. I have dabbled with Lilypond, and it seems like a similar process might be possible in that program. I consider myself to be a highly proficient user of Sibelius v6, but there are lots of nooks and crannies in that program that I have yet to explore. What I can say, is that I started with an ultrafull score this morning at about 7 a.m., made a few final corrections to it, and then started extracting parts. By 10:30a.m., I had 35 parts saved as PDF files for a 4-minute concert band piece. Tomorrow, I will give them a final proofread, and then send them off. Making them was a little bit tedious, and I was glad to take a break to make breakfast for myself and my kids, but it all went very smoothly in the end. Within a month, the commissioning band will be reading from the parts I created this morning, and my goal of bringing a new piece of music to a fantastic group of people, some whom I have known for years, and some who will be playing my music for the first time, will have again been accomplished.